A re-awakening

by Rabbi Dr David Fox

She really was doing her best. As the clinical manager on the psych ward, it was her job to keep the treatment programmes flowing, to ensure that all patients participated in their assigned treatments and activities, and to be a supportive advocate for those patients who needed special attention. She managed to find a room for the man who was allergic to monkeys which was not near the room of the delusional man who believed his pet monkey had followed him to the hospital. She made sure that the recovering addict stopped telling other patients who he actually was, because his celebrity identity would have caused commotion. The woman who hammered on the walls all night because she said they were her drums was placed in an insulated room where no one heard her pounding. And the eastern mystic…well, he was another story.

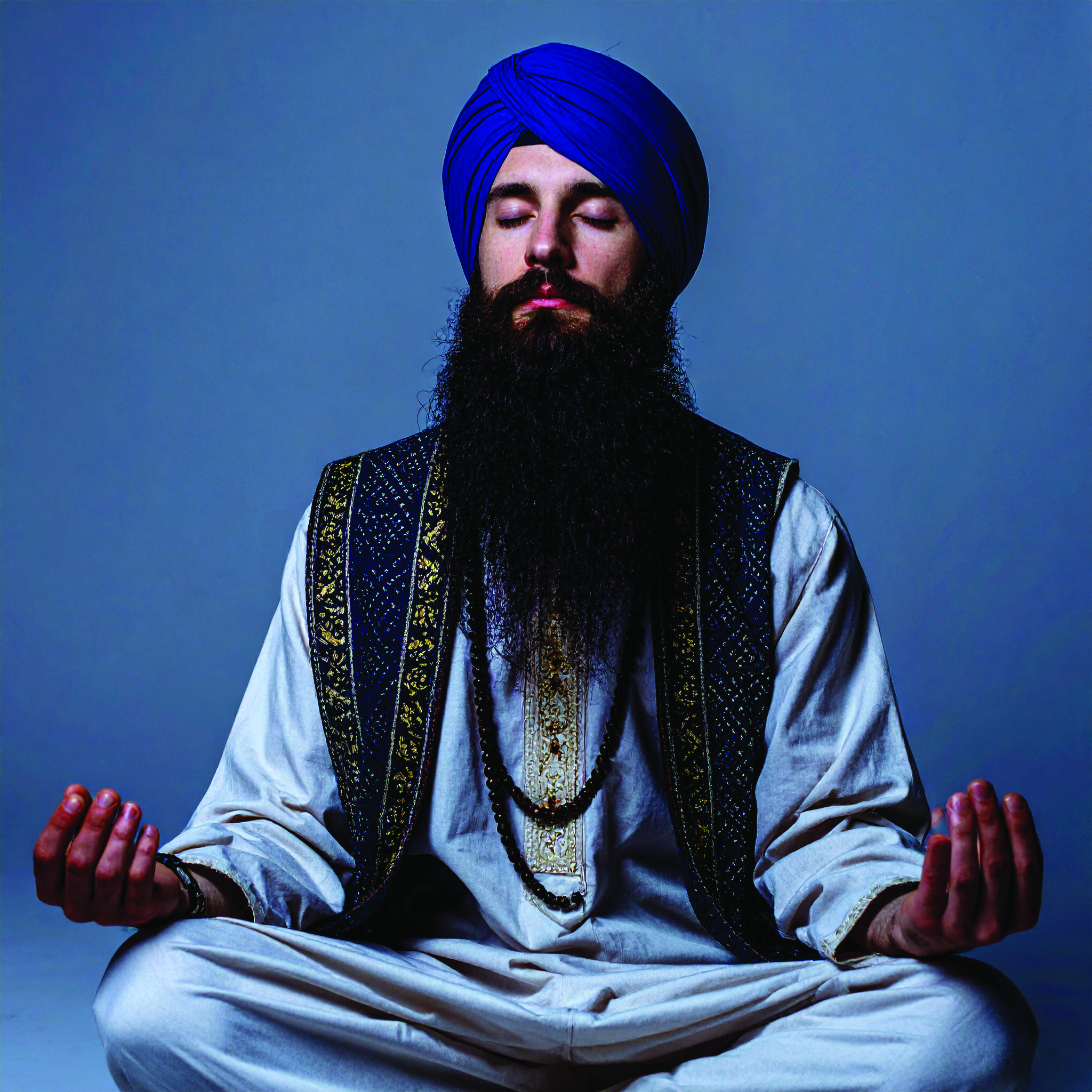

A man had been hospitalised by his family because he was overly absorbed in a religious cult; harmless, but decidedly out of synch with mainstream practices. He wore a long colourful robe with matching turban, his beard had not been cut for years and reached nearly to his knees, and he had taken a vow of silence long ago. He spoke to no one, he made no eye contact even when he did open his eyes which was rare, he sat on the floor on a mat most of the day and night and seemed to drone a monotone while doing some type of meditation. He ate only boiled rice, would not touch other patients or staff nor converse with them, and wanted his solitude and silence. The clinical manager conferred daily with the treating staff in attempting to determine what type of treatment he needed, if any. His parents had had him brought to the facility by ambulance because he had been on a fast for weeks and was now emaciated. They had sent a report from a family doctor who had determined that this son had made a break with reality by adopting this lifestyle. They feared that he was schizophrenic and a danger to himself. However, there were no records of treatment because he had been in the far east living on some type of commune and had only come home because his parents had threatened to discontinue paying for his lifestyle unless he had an evaluation.

So, weak and gaunt, he had agreed to be driven to the hospital, was admitted to the psych ward for observation, and was making it difficult to evaluate him because he interacted with no one and said nothing but that deep throaty hum. There was no history to go on, no records to study, and not even information about his family who wanted little to do with him until he, in their eyes, normalised.

A few days later, a new patient was admitted to the ward. This one was trouble. He was loud, obtrusive, and riled others up. He would start arguments, insult others, and was at all waking hours disruptive. He was assigned to some treatment options and otherwise roamed the halls of the ward making noise. A few times, the clinical manager had to intervene when he would pester a depressed patient or would taunt an agitated one. Still, he roamed the ward almost looking for trouble. It was then that he spotted the meditator sitting crossed legged on his mat, palms on his lap, eyes shut, and chanting his monotone. Mystified, the loud one was silenced, staring at this new target with a grin. He stood there looking at him, then began stomping his feet, beating his hands on a table, and shrieking like a wild man. The staff froze, waiting for a showdown. The clinical manager waited to see what would happen. After the cacophony endured and the shrill yelps of the noisy man grew louder and his beat on the table became a booming staccato, the mystics eye’s fluttered open. He quickly took in the scene. His trance had been broken, and his rocking back and forth came to a halt.

It was then that two words escaped his lips: “Sha! Shtill!” he demanded in Yiddish. The Jewish staff stifled their grins. The Jewish patients scratched their heads, as the other patients looked puzzled, wondering what those “eastern” words meant. Meanwhile, the clinical manager made some notes in the man’s file and finally began to carve out a culturally sensitive treatment plan for this enigmatic character, who was returning home at last.

Rabbi Dr David Fox is a forensic and clinical psychologist, residing in Los Angeles, where he is also a rav and rabbinic lecturer, a published author, and graduate school professor. He regularly serves as a dayan on the rabbinical courts of Jerusalem and in the United States, and has authored responsa on the four portions of Shulchan Aruch. He is the Director of Interventions and Community Education of Project Chai, the Crisis, Trauma, and Bereavement Department for Chai Lifeline International. He can be reached at: dfox@chailifeline.org